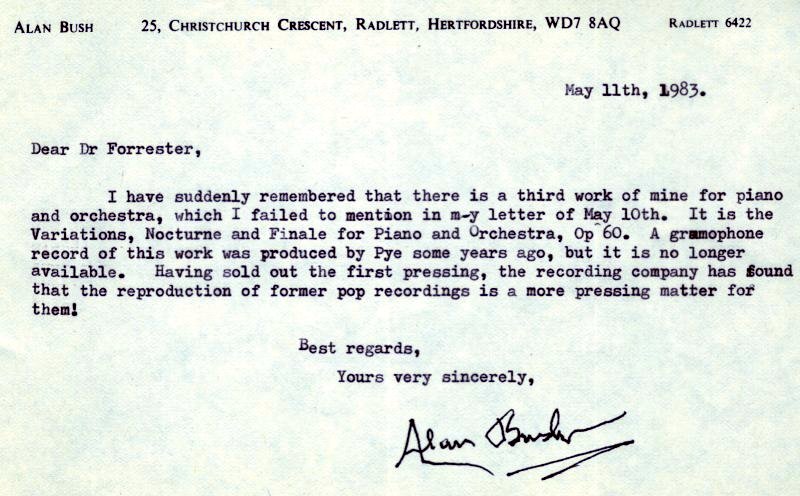

A Signed Letter

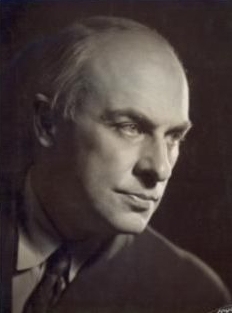

Alan Bush (1900-1995)

I've been interested in the music of the British composer Alan Bush for over 15 years now, ever since I found (and bought) this signed letter in the specialist music bookshop May & May Ltd.

This letter sparked my interest in a composer about whom I knew nothing - even though I was familiar with a fair amount of English music from the late 19th and first half of the 20th century - particularly the music of Elgar, Vaughan Williams, Holst, Delius, Walton and Bax.

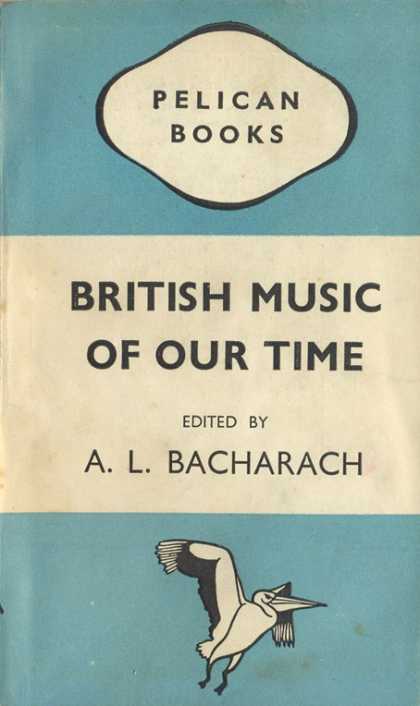

At that time it seemed to be quite difficult to find out much about Alan Bush. Besides a few very brief entries in musical dictionaries and encyclopaedias there was very little information readily available. I think the most detail I first saw was this short passage in an article by Robin Hull in the 1946 book British Music of Our Time:

From British Music of Our Time

edited by A. L. Bacharach, Pelican Books, 1946

The music of Alan Bush (b. 1900) plainly requires, for a successful approach, those careful and repeated hearings made possible by gramophone records, or, at the least, by public performances of tolerable frequency. It must be owned that, up to the present. Bush has been very insufficiently served in both these regards. Of course this circumstance may be remedied at any moment, as it ought to be, but meanwhile the problem of access remains needlessly severe. Yet perceptive music-lovers enabled to hear even one performance of a work so boldly individual as Bush's Dialectic for String Quartet can scarcely fail to be struck by the outstanding force of its intellectual power. The music is conceived with a virility of purpose fully realised in the address. The very urgency of the argument requires tension in its delivery, but this tension is always under drastic control, and never slips in the direction of emotional oratory. An interesting point for the listener is that this refusal to misuse emotion does not involve the smallest loss of variety in Bush's pages. The effect is rather as if different sections or stages of the argument demand a corresponding change of voice, yet such changes are invariably consistent with the whole. So far as the reader finds himself afforded any option in the matter, the Dialectic is certainly a first choice in trying to measure Bush's style at its true strength. The main problem in listening is likely to devolve much less upon the nature of the musical language, which is not only extremely direct but very clearly employed, than upon a swift assimilation of such potent subject-matter. It is more than possible, indeed, that a first or second hearing may not reward the listener as quickly as he desires, but there are good grounds for suggesting that any such experience will arise almost entirely from conciseness of Bush's material.

The Symphony in C demonstrates vividly, as those who have had a chance to judge may endorse, that this composer's powers are equal to sustaining invention upon a very big scale. He is one of the relatively few who have mastered the secret of "going on" when dealing with a large structure; that is to say, he is nowhere thrown back upon the device of skilful joinery to conceal an untoward transition. The day has long been overdue for a revival of this Symphony, and also for a hearing of the Piano Concerto (with baritone solo and male-voice chorus in the last movement) which, through no fault of their own, remains a closed book even to those who would rightly value performances.

Another piece of information that caught my attention was that Alan Bush's music was banned by the BBC for a period during the Second World War - from March 1941 until 22nd June 1941. The ban was put in effect because Bush was a signatory to The People's Convention.

The People's Convention, 1941

The People's Convention was first held on 12th January 1941. It was essentially an eight-point programme, supported by a fairly broad spectrum of the British Left, to focus disapproval of the handling of the War by Neville Chamberlain's Government. It called for

- Improved living standards

- Improved air-raid shelters

- Restoration of civil, democratic and trade union rights

- Implementation of emergency powers to run banks, agriculture and industry

- Friendship with the Soviet Union

- Establishment of a People's Government

- Self-determination for the Colonies

- A People's Peace to enable people of all countries to determine their own future

Action on these points was taken by local and regional committees, through public meetings and publication of leaflets and newsheets.

The Convention folded at the end of 1941 - it's objectives became overshadowed by events and, to some extent, irrelevant after the invasion of the Soviet Union by Germany on 22nd June 1941.

Ralph Vaughan Williams spoke out against Alan Bush's ban in a strongly worded letter to the Director General of the BBC.

Alan Bush died in 1995; the following obituary gives a concise summary of his life. For more information on his life or work I cannot hope to compete with the superb web site of the Alan Bush Musical Trust.

Alan Bush Obituary

From The Times, Saturday 4th November 1995

Alan Bush, composer and Professor of Composition at the Royal Academy of Music, 1925-78, died on October 31 aged 94. He was born on December 22, 1900.

Of all the 'isms' that can be hung around the neck of a composer none has been more oppressive than the label of Marxism. Alan Bush had joined the Communist Party in 1934 and probably knew as much about Marxism as anyone in Britain. Philosophy, beside music, had been a lifetime's study. But he innocently accepted Marxism's corruption by the oppressive regimes of Eastern Europe. And by his choice of radical texts and titles, so easily mocked, he perhaps drew attention away from the high quality of the music itself. Despite the evident enthusiasm for his work of critics as severe as Hans Keller or fellow composers such as Michael Tippett and William Alwyn, the wider audience of 'the people', for whom as a Marxist he wrote, was rarely given the chance to experience his music. An opera such as his Wat Tyler of 1951, though eminently English in its appeal, was given its first stage performance in Leipzig in East Germany.

Alan Bush was born in London. His outstanding gifts as a pianist took him to the Royal Academy of Music, where he studied composition with Frederick Corder, and the piano with Tobias Matthay.

Many composers come to music through the piano, but touch it only in the privacy of their workroom; Bush, like Bartok and Britten, relished his skill he even seemed to enjoy a daily workout of studies and scales. His Opus 1 and his earliest published composition was a set of three pieces for two pianos, followed in the same year by his Piano Sonata in B minor. Several chamber works followed, culminating in what some still regard as his finest abstract piece, Dialectic for String Quartet, completed in 1929 but not performed until 1935.

In 1929 he enrolled as a student in the philosophy department of Berlin University, where in two years he mastered not only the German language, but also developed the analytical skill which could delight or dismay his students. But his fingers were still active he gave a demanding solo recital at the Berlin Singakademie in 1931.

On his return to England, Bush threw himself into organising and conducting popular choral concerts. In 1936 he took a leading part in the foundation, and as its first president, in the running of the Workers Music Association. In 1938 when his Piano Concerto with a rousing choral finale was premiered by the BBC, the conductor, the highly traditionalist Adrian Boult, cut short the applause by playing the national anthem.

During the war Bush served as a private in the Royal Army Medical Corps, but this did not save him from having his works banned by the BBC in the early part of the war because of his communist sympathies. (This was at the time when the Nazi-Soviet Pact had not yet been shattered by the German invasion of Russia.) When Bush pointed out to a BBC official that the works of enemy composers such as Richard Strauss had not suffered the same fate, he was told that Strauss was not being paid by the BBC.

After the war Bush began to simplify his style in an attempt to reach out to a wider audience. Many of his choral works were set to radical texts, but none is more touching than his Christmas Cantata, The Winter Journey (1946), for soloists, chorus and chamber ensemble.

Bush's first symphony was completed in 1940, the second, a commission from the City of Nottingham in 1949, and his third, with a choral finale dedicated to the memory of Byron, in 1960. There is also a fine violin concerto and other works for string as well as full orchestra.

But Bush's major contribution was as an opera composer, with his wife Nancy (nee Head) as librettist. His first full opera, Wat Tyler, was one of four prize winners in the competition arranged by the Arts Council for the Festival of Britain in 1951. It was broadcast in a recorded performance from East Berlin in 1952 and first staged in 1953 in Leipzig where it had 14 performances. It was done in Rostock in 1955, but it was not until 1974 that it had its first professional production in England, at Sadler's Wells.

Bush received three more commissions from Leipzig, but only one of these, The Men of Blackmoor, was ever staged in England where it received a production by the Oxford University Opera Club in 1961 (it had been first produced at Weimar in 1956). The Ferryman's Daughter (1964) was for schools; The Sugar Reapers was done in Leipzig in 1966; and Joe Hill (The Man Who Never Died) was staged in Berlin in 1970.

As a teacher he was firm in conviction, consistent in style, clear and logical in thought, direct in expression, and warm in feeling, as generations of students who passed through his hands would attest. Bush had an ear for lyric beauty, and a feel for drama that make his operas powerful experiences. But he had to contend with an apathetic music establishment, as well as hostility to his passionately held beliefs. In the post war years, when he might have benefited from the great expansion of musical life, the rise of a radical avant-garde kept out Bush and his like, still committed to a more traditional aesthetic.

Availabilty

If it was hard to find information about Bush, it was next to impossible to find any available recordings of his music. It must have been a couple of years until I managed to hear a couple of performances on the radio. This situation is now improving - there are a few CDs now available of his music, particularly of the chamber music, piano works and songs. I have yet to hear performances of any of the symphonies or operas.